We live in interesting times. The famed ‘fast changing world’ – the best we can do to describe the overwhelming whirl of evolution as it gathers pace.

I believe that we’re in the midst of the early chapters of a new age. Ken Wilber calls it integral. James Altucher would call it “choose yourself”. Seth Godin talks about the connection economy. I used to think of it as the age of the realized entrepreneur. I think I was half right.

Our ideas of professional work are in the midst of great flux. The professional used to be someone who had a trade – a craftsman, farmer, healer, soldier. Then it was a job was had, with a contract and a role, and a boss.

Now the standard is more like a vocation, which originally means calling. It’s professionally answering the call to the higher, to the gods, to what burns deep inside your heart.

The enactment of this new professionalism is transformational by nature, that is, by following the call of the gods, we must become someone new and travel the mythological hero’s journey.

The hero isn’t a person, the hero is an archetype – the one who hears the calls, steps onto the path, and is initiated into their higher self through great challenge. It is the sacrifice of comfort for the greater realization of your reason for being here.

This is not an abstract concept. It is the thing that happens to us all, if we consent. Or even sometimes when we don’t. It was a hero’s journey for me 6 years ago when I decided to leave the comfort of employment at a fast growing internet company, and leapt into the unknown, with some vague notion of being an entrepreneur and talking about consciousness.

It’s what it takes to write a book that bears genius in its pages. It’s what Steve Jobs must have had to go through to return to Apple after being fired, and creating the first iPhone.

The map I present in this article is my attempt to show you who this hero is, or more precisely, what makes each of us heroic, and how we can use this map to better navigate our own journeys and transformations.

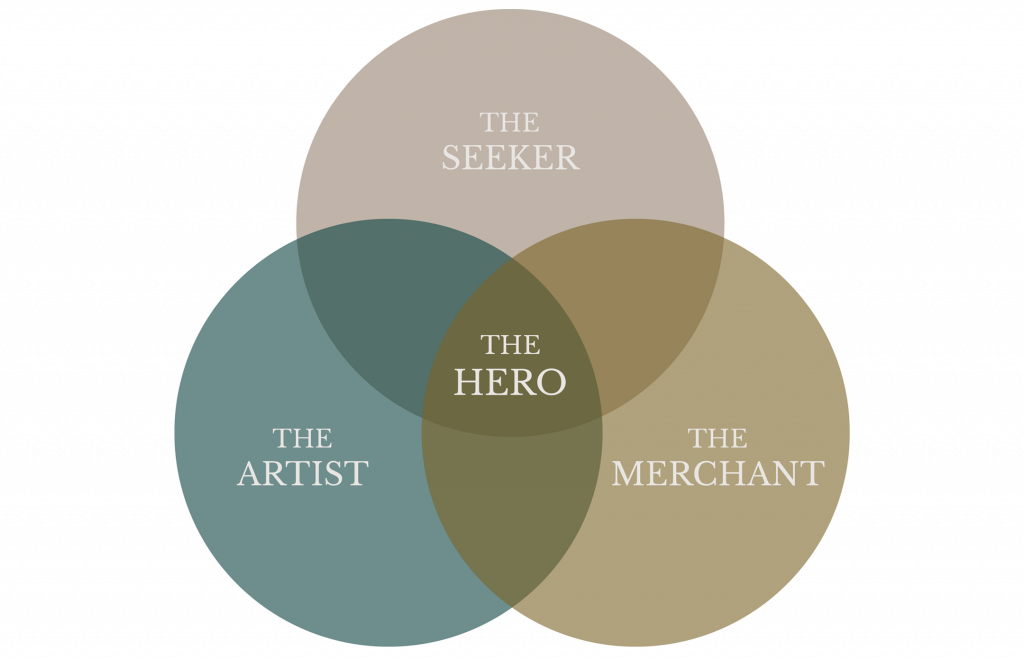

This is the hero as I see it, the intersection of three fundamental professional archetypes – the seeker, the merchant and the artist.

And it is the roots of this archetypal trinity that I will begin my story with.

The philosophical roots of being

Running throughout philosophy – from the Bhagavad Gita, through Plato, through Immanuel Kant, through Jurgen Habermas and up to the present day – is a triadic structure that under various guises, has been presented as deeply intrinsic to reality.

The ancient Greeks thought of the three domains of life – art, morals and science, and the three transcendentals that related to them. Karl Popper called them the objective, subjective and cultural. Kant wrote his three great critiques.

Ken Wilber, whose work first introduced me to this pattern, ties them to universal pronouns – I, We and It. He calls them The Big Three. They are the first demarcations we make in the oneness of reality. They are that fundamental.

For Plato they were the good, the true and the beautiful. And it is that frame I want to use here.

The three languages

You can think of these three ideas – the good, the true and the beautiful – as three languages.

Each one fundamentally different from the last, and yet each one fundamental to human experience. That is – one language cannot describe the territory of another language. Yet each one is part of the whole, and so where one finds truth, one will also find beauty, and goodness.

“Words which give peace, words which are good and beautiful and true, and also the reading of sacred books: this is the harmony of words.”

– Bhagavad Gita, 17:15

To find the harmony in the three, you must learn to hear the individual melody of each language. For the language of truth, cannot tell us what is beautiful. The language of goodness cannot tell us what is true. The language of beauty cannot tell us what is right and just.

The True

The language of truth is the language of discovery and precision. It is the language of deep science – that deliberate and practical means by which we test the world, and ourselves, and discover ever deeper truth about its reality.

It is something we uncover and reveal, it is something that we posit and falsify. The language of truth seeks to gently or forcefully, spear the squirming fish of meaning, and define its patterns and structure.

Is it true that human beings evolved from higher apes? Yes. It took us a long time to discover this truth. But it’s now self evident for most fo the world.

Is it true that if I spend enough time looking into the nature of my own experience, I will be unable to find the location of my own consciousness? Yes. I’ve tried. Like thousands of yogis and roshis. It’s not in my head, it’s not in my toes. It doesn’t even seem to limited to my body. It’s kind of everywhere and nowhere.

When we seek the truth, we must attack and destroy our own assumptions about what is. We must bind together polarities that feel uncomfortable, and find harmony in the integration of relative truths. This frees us, and liberates our notions of what is possible, and who we are.

“And you will know the truth, and the truth will set you free.”

– Jesus of Nazareth, John 8:32

Ken Wilber’s famous phrase is that “everyone is right”. Every single human perspective has some partial truth. But for that to be true, we must also hold that some are more right than others.

The great seekers of truth understand this, they constantly seek for greater truth that transcends the partial truths.

“He who knows only his own side of the case knows little of that. His reasons may be good, and no one may have been able to refute them. But if he is equally unable to refute the reasons on the opposite side, if he does not so much as know what they are, he has no ground for preferring either opinion.”

― John Stuart Mill, On Liberty

Truth is an objective science, whether the terrain physical, conceptual or mystical. Mathematics is a dialect of truth. The Tao Te Ching is a treatise on mystical truth. Cartography is mapping physical truth.

To know what is true, reality must be examined, tested and mapped.

The Good

Whether any of this is a good thing is an entirely separate question.

The good is the language of ethics. What is right, just? How do we know? It is not an objective science – it is not a solitary investigation. It is a collective exploration of our own ethical principles. The codes by which we feel it is right to live.

“To prefer evil to good is not in human nature; and when a man is compelled to choose one of two evils, no one will choose the greater when he might have the less.”

– Plato, The Protagoras

Is it good that many people still suffer, and struggle to have enough to live? No. I don’t know anyone who thinks that’s a good thing.

Is it good that the homicide rate in the West are at their lowest rate in recorded history? Yes.

Is it good that we have ever more free markets? That’s tough. I’d say yes. Many would say no. It’s an unknown. We’re still in the conversation.

“Morality is not just any old topic in psychology but close to our conception of the meaning of life. Moral goodness is what gives each of us the sense that we are worthy human beings.”

– Steven Pinker

The language of the good is relational. You and I have a conversation, create mutual understanding, and thus form a We – something greater than the sum of its parts. And in that collective We, decide what we think is just and right. It is not scientific. It is not subjective. It is inter-subjective.

To decide what is good, we must engage in a conversation about how we want to live with one another.

The Beautiful

When we ask what is beautiful, we enter the domain of art. It is about expression and provocation. It is the ultimate subjective world. For beauty is in the eye of the beholder, and the I alone.

Beauty cannot be scientifically tested – it cannot be proved to be true or false. No one can declare that the Mona Lisa is officially ‘beautiful’ or that Star Trek is not.

Nor can it be said to have moral foundation. Is it good that Tolkien spent two decades making up Middle Earth, and writing The Lord of the Rings? It’s the wrong question.

The question is, did it change your experience? Were you struck by it? Did it leave you with a question mark in your experience?

“We can slip into the Beautiful with the same ease as we slip into the seamless embrace of water; something ancient within us already trusts that this embrace will hold us.”

– John O’Donohue

Beauty is the ultimate subjective experience. The phenomenological aesthetic. An expression of something utterly indescribable, and yet instantly recognizable.

How can you describe the language of a sun set? The untranslatable feeling of looking out as our great star sinks once more behind the horizon, as it’s done since the beginning. Writers have spent centuries to describe the beauty of a sun set, and none of them have nailed it. We can never nail it.

Beauty is what is all around us, we know it intimately, and yet to capture it, is to capture the most striking and elegant butterfly. As soon as it’s in a net, it becomes less beautiful.

“Never lose an opportunity of seeing anything beautiful, for beauty is God’s handwriting.”

– Ralph Waldo Emerson

To see what is beautiful, I must look with my own eyes.

The three archetypes

It is these languages that the three archetypes – the seeker, the merchant and the artist, speak in.

These are not the only branches that grow from the roots of the languages. These are what I have come to think of as the professional dimension of these three languages. That is, how do the good, the true and the beautiful, show up in the domain of contemporary work?

The Seeker

The seeker seeks truth. Whether it is the deep spiritual truth of Adyashanti or the deeply human truths of Brene Brown, the impetus is to explore the unexplored, map the terrain, and come back to teach us.

“It is not the possession of truth, but the success which attends the seeking after it, that enriches the seeker and brings happiness to him.”

– Max Planck

It’s manifest in the Tibetans who sat in caves in silence for thousands of years and developed the most exquisite maps of human consciousness. It’s the Victorian explorer who braved the dangers of uncharted seas and discovered new lands. It’s the physicist who finds new theoretical models that explain the unexplainable.

In the professional arena, it is the seeker who shows us the way. Their brilliant mapping of difficult things gives us a path through the struggle. Their unquenchable thirst for deeper understanding keeps us curious, humble, and constantly learning. It could be a scientific seeking of truth, like Tim Ferris. It could be mystical seeking of truth, like the Dalai Lama.

The vice of the seeker is pride – the seeker who claims to have found the truth, a truth no-one else has. They revel in it, boasting of the truth they know, denigrating the truth of others.

It is the spiritual teacher whose existential arrogance leads them to outrageous claims, or relational abuse. It is the scientist who refuses to believe any kind of truth other than his paradigm, disparaging claims that fall into a different language or dialect.

The mature seeker understands that they are an instrument for truth, using themselves to understand ever deeper and more elusive truth that they share for the benefits of others.

Famous Seekers

Jesus Christ, Albert Einstein, James Cook, Brene Brown, Adyashanti, Tim Ferris, Isaac Newton, Christopher Columbus, Alan Watts.

The Merchant

The merchant trades in the good. Whether it is the material goods of Wholefoods or the political goods of Barack Obama, the conviction is the same – that trading goods benefits everyone.

“Man is an animal that makes bargains: no other animal does this – no dog exchanges bones with another.”

– Adam Smith

Trade happens between people. It is an intersubjective conversation about trust, permission and integrity. To trade, you have to believe the other person has good intentions. When they do, and you do too, more good is created, more ethical wealth is generated. The world becomes richer, in materials, freedom and culture.

In the professional arena, it is the merchant that knows how to scale their impact, to bring their goods to ever increasing numbers of people, or at ever increasing depth. The merchant is the innovator who who builds brilliant new apps, or the marketer, who knows how to speak to their audience.

The great vice of the merchant is greed – they use their mercantile skill, subterfuge and manipulation to extract maximum value for them self, at the expense of everyone else. This is the Victorian factory that uses its workers as expendable cogs in an industrial machine.

They have forgotten that what is good is only determined in fair and transparent marketplace of goods and ideas, where we decide together, what is ultimately valuable, just and good.

Famous Merchants

Adam Smith, Steve Jobs, Seth Godin, Bill Gates, Warren Buffet, John Mackey, Jeff Bezos, Henry Ford.

The Artist

The artist creates beauty. Whether it is the mystical beauty of Leonard Cohen or the magical beauty of Neil Gaiman, the compulsion is to make something from nothing, and touch us.

“Every human is an artist. The dream of your life is to make beautiful art.”

– Don Miguel Ruiz

The artist follows an invisible design, obscured even from the artist them self. It reveals itself as the artistic path is followed, and the picture comes as if from the page.

Art happens in the spaces between things. The afternoon left free of appointments, and a song on the radio inspiring a burst of new writing for hours. It happens when you walk in the park, enjoying the beauty of the birds playing in the trees, and something moves in you.

In the professional arena, the artist is the one who creates things. Through some mysterious process they produce artifacts – writing, paintings, music, design – that touch people and change things.

The artist’s great sin is envy, or more precisely, the great fear that they are in truth, mediocre, one of the bottle, not special. And so to spare them this great pain, they seek to acquire the prestige or standing of others around them.

They forget that beauty is seen through the eyes of the gods, and instead, judge their beauty through their own narcissistic eyes. They replace the great I for the small I, and endeavour to prop up their own ego by being the most beautiful person, rather than the person who creates the most beauty.

Famous Artists

Michelangelo, Neil Gaiman, Leonard Cohen, William Shakespeare, John Lennon, Rumi, Darren Aronofsky, Rainer Maria Rilke, Herman Hesse.

The hero of a new age

These are three fundamentally different vocations. They are based on languages that describe three fundamentally different worlds. And while each of us will be a native speaker in one archetypal language, the goal is to integrate these three archetypes in you, infusing their worlds into your work.

Never has there been a time when integration across these three worlds has been more needed or more possible. This I believe, is the professional imperative of our age.

Now I have given you a simple map, can you see where you are on it? What is your native language? Which is most foreign to you? Where do you have tension between the types?

I am a native artist. And for most of my life, the world of the merchant was completely foreign to me. Much of my personal work over the last few years has been to integrate the merchant more deeply into my work.

This is the first part of the map – the outer three archetypes. In part two, I will explore the fourth archetype – the hero – and how it relates to this trinity of the seeker, the merchant and the artist.

For the hero is you, the future you, that is yet to be created through the journey of transformation. And to be a professional hero, is I believe, the vocation of this new age.

Join the conversation